Modern Nature (Prospect Cottage)

- likely a pun on prospect as "view" and as "future"

1989

JANUARY

Sunday 1

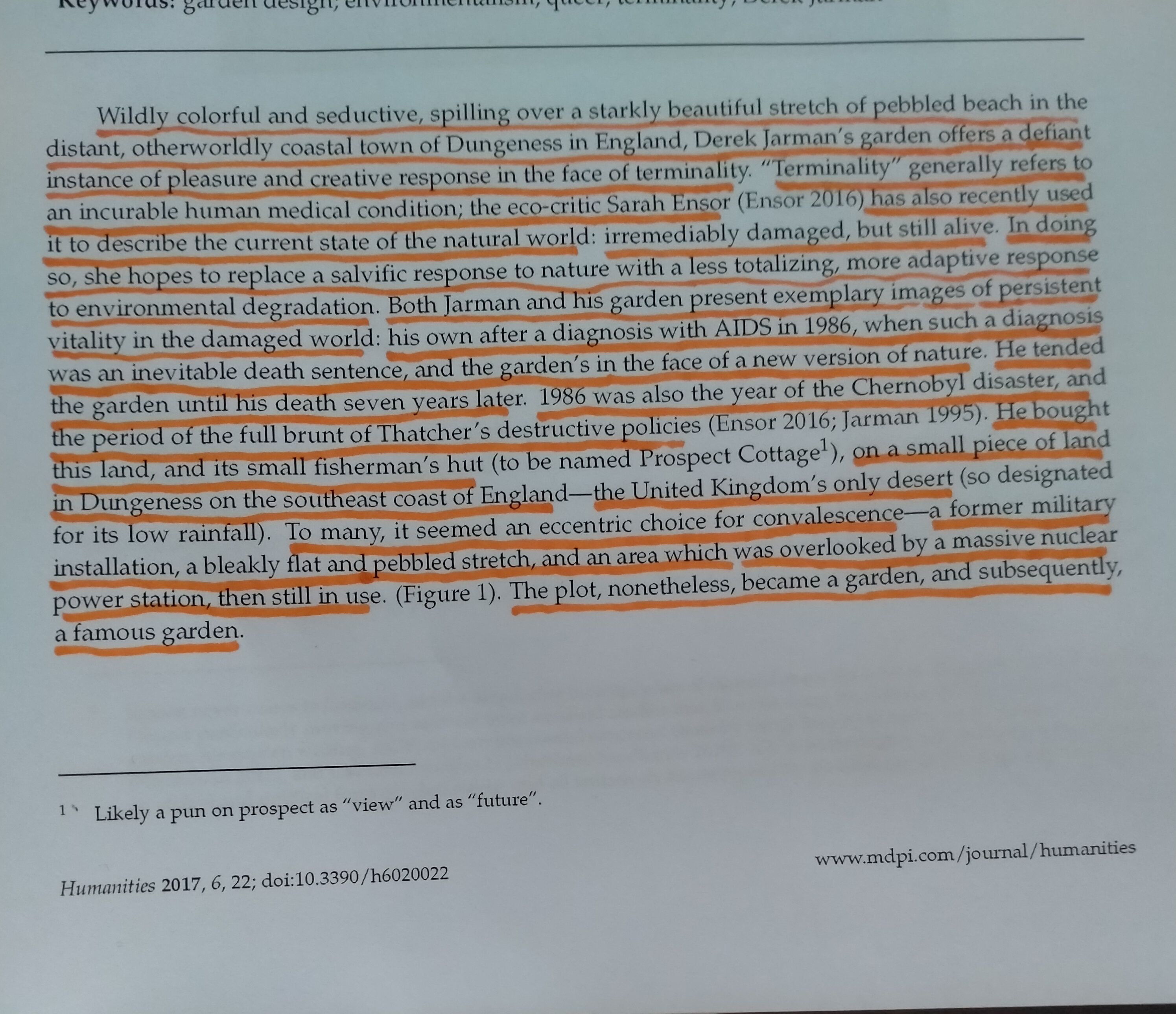

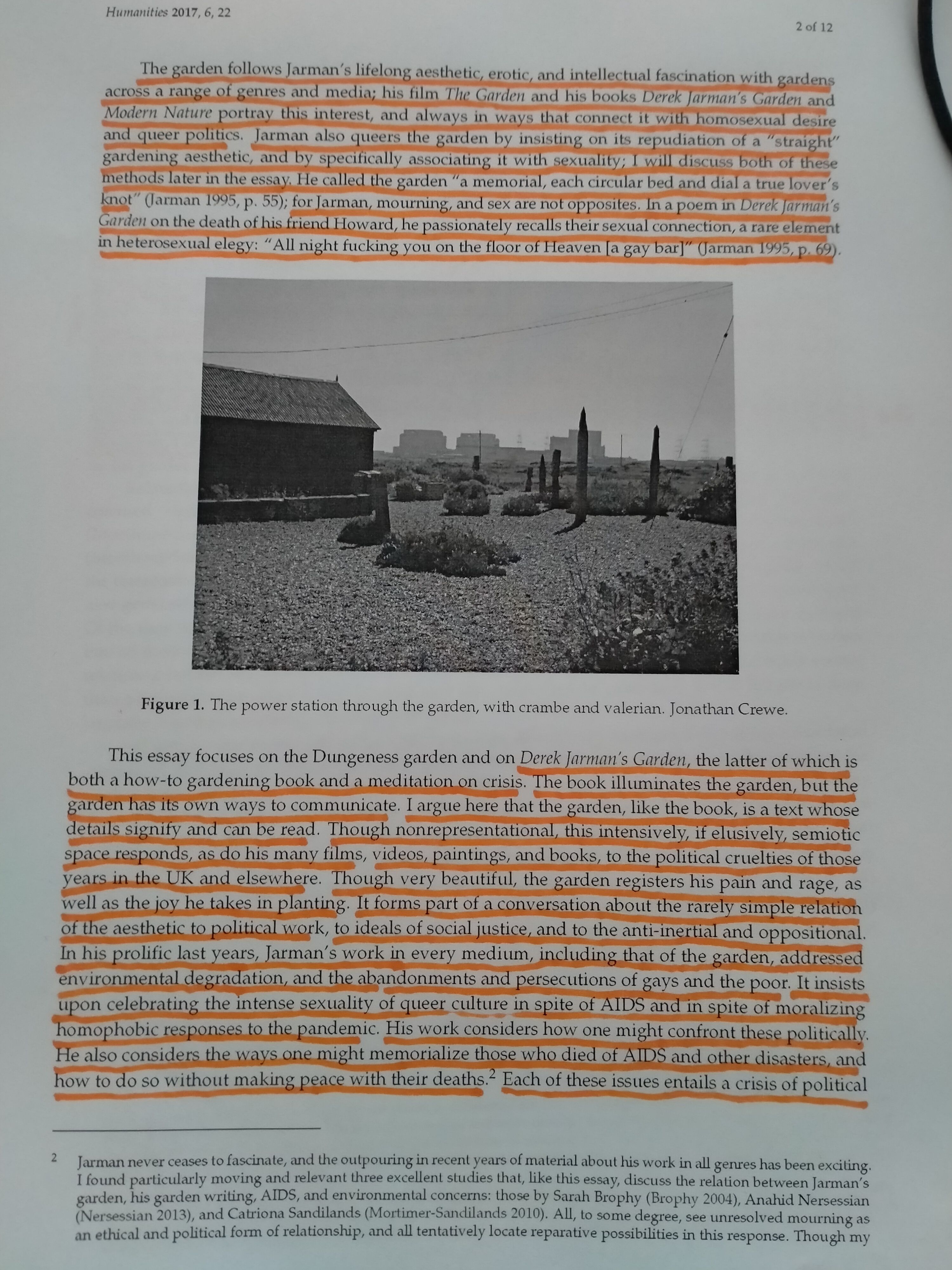

Prospect Cottage, its timbers black with pitch, stands on the shingle at Dun- geness. Built eighty years ago at the sea's edge - one stormy night many years ago waves roared up to the front door threatening to swallow it ... NOWT the sea has retreated leaving bands of shingle. You can see these clearly from the air; they fan out from the lighthouse at the tip of the Ness like con- tours on a map.

Prospect faces the rising sun across a road sparkling silver with sea mist. One small clump of dark green broom breaks through the flat ochre shingle. Beyond, at the sea's edge, are silhouetted a jumble of huts and fishing boats, and a brick kutch, long abandoned, which has sunk like a pillbox at a crazy angle; in it, many years ago, the fishermen's nets were boiled in amber pre- servative.

There are no walls or fences. My garden's boundaries are the horizon. In this desolate landscape the silence is only broken by the wind, and the gulls squabbling round the fishermen bringing in the afternoon catch.

There is more sunlight here than anywhere in Britain; this and the con- stant wind turn the shingle into a stony desert where only the toughest grasses take a hold - paving the way for sage-green sea kale, blue bugloss, red poppy, yellow sedum.

The shingle is home to larks. In the spring I've counted as many as a dozen singing high above, lost in a blue sky. Flocks of greenfinches wheel past in spirals, caught in a scurrying breeze. At low tide the sea rolls back to reveal a wide sandbank, on which seabirds vanish like quicksilver as they fly close to the ground. Gulls feed alongside fishermen digging lug. When a winter storm blows up, cormorants skim the waves that roar along the Ness —throwing stones pell-mell along the steep bank.

The view from my kitchen at the back of the house is bounded to the left by the old Dungeness lighthouse, and the iron grey bulk of the nuclear re- actor —in front of which dark green broom and gorse, bright with yellow flowers, have formed little islands in the shingle, ending in a scrubby copse of sallow and ash dwarfed and blasted by the gales.

In the middle of the copse is a barren pear tree that has struggled for a century to reach ten feet; underneath this a carpet of violets. Gnarled dog roses guard this secret spot - where on a calm summer day meadow browns and blues congregate in their hundreds, floating past the spires of nettles thick with black tortoiseshell caterpillars.

High above a lone hawk hovers, while far away on the blue horizon the tall medieval tower of Lydd church, the cathedral of the marshes, comes and goes in a heat haze.

A sky blue borage plant in flower, one of a clump that self-seeded by the back door. It droops in the early morning frost but recovers quickly: 'I bor- age bring courage.'

(Modern Nature Pag. 3-4)

April (1989)

Wednesday 26

The hawthorn and birch are in bright green leaf; the pear is in blossom; the ash tree buds are breaking. The primrose and violets are disappearing till next year under invading nettles. As I walk past, the snobbish wheatears complain – tch! tch! – in the flaming gorse.

Spring dances on in soft white clouds.

∼

Ministers attend a seminar on global warming.

∼

(...)

(...)

There's a menacing sunset beyond the nuclear power station: livid yellows and inky blacks with a deep scarlet gash. As shadows close in, the landscape turns grey; the sky has sucked up all its colour. An icy wind gets up – rain before night's end is forecast.

∼

They say the answer is more nuclear power stations.

∼

(...)

(...)

Our little wood shivers. What of the earth below these angry skies? A tree goes, a road is widened, a meadow ploughed, more quarries, another house. (JARMAN, Modern Nature, p.67-68)

February 1989

Friday 3

(...)I was describing the garden to Maggi Hambling at a gallery opening. And said I intended to write a book about it.

She said: 'Oh, you've finally discovered nature, Derek.'

'I don't think it's really quite like that,' I said, thinking of Constable and Samuel Palmer's Kent.

'Ah, I understand completely. You've discovered modern nature.'

In July my bank bloomed with two distinct wild poppies —the long headed poppy, P. dubium, and the field poppy, P. rhoeas. I carefully gathered the seed heads and raked the mound - as poppies like to grow in newly dis- turbed soil. The rest of the seed is scattered far and wide . . . Some of the seedlings are already two inches across, but the slugs seem particularly fond of them and continually crop them; they survive though, and are soon sprouting again.

I filmed last year's poppies with a bee hovering over them and put the shot into War Requiem. Poppies have sprung up in many of my films: Imagining October, Caravaggio, The Last Of England and War Requiem.

Scarlet Poppies

This is a poppy

A flower of cornfield and wasteland Bloody red

Sepals two

Soon falling

Petals four

Stamens many

Stigma rayed

Many seeded

For sprinkling on bread

The staff of life

Woven in wreaths

In memory of the dead Bringer of dreams

And sweet forgetfulness

(Modern Nature, PAG.8 - 9 )